World War 1 made unprecedented demands on those who fought in its battles. The day to day fighting depended on the physical and emotional strength of men. These men, in countless ways, depended on animals. This is the story of Stubby, of the 102nd Regiment of the American Expeditionary Force.

A stray pit bull terrier roaming the streets in New Haven, Connecticut found his way onto the parade grounds of Yale University. One morning, a young soldier, John Robert Conroy spotted the young pup and took him in as a pet. Upon examining the dog, Conroy took notice of his stub of a tail. “Stubby”, Conroy decided, would be the dog’s name.

It didn’t take very long for Conroy and his fellow soldiers to recognize the dog’s exceptional intelligence. Stubby watched the men for weeks, observing their behavior, and learning to recognize the orders they were given. Not long after, Stubby joined the men on their marches, keeping a perfect beat with his master. The dog wasn’t done training himself, not at all.

Unfortunately, the training at Yale would have to end. When it came time to deploy, Conroy knew he couldn’t simply leave the beloved dog behind. Conroy smuggled the dog aboard the ship to France. It worked well, albeit only for a few hours. When it was time for roll call, Stubby watched as his friends drew their hands to salute. He wanted to salute as well, and went to line up with the men. Stubby darted from his concealed carrier and drew his paw to his brow. The commanding officer was astonished. It was decided not long after that the dog would be allowed to serve on the battlefield.

Stubby’s official role was the mascot, but that would soon change. Stubby was critically injured in 1918 during the fighting in France. Mustard gas, the infamous chemical weapon which caused so much suffering, filled the little dog’s lungs. However, this was no ordinary pit-bull. Stubby recovered in a few days, returning to the battlefield with an ability that saved hundreds. The ability to detect the gas before it became lethal. From that moment forward when gas was launched, Stubby would sprint up and down the trench, harassing the men until they would equip their gas masks. Not having a mask to equip himself, Stubby would retreat once the gas was too much for him to handle. Stubby’s battlefield senses didn’t end there. The whistling of artillery as it soars through the air was recognizable to him long before it would have been to the men, and upon hearing it, Stubby would bark and point his paw to the sky.

After surviving a hand grenade in Germany, Stubby arrived in the Argonne Forest in September of 1918. Sometime in the evening, Stubby picked up the scent of someone he didn’t recognize. A German spy nestled inside a shrub near the American trenches. Stubby yowled and barked for half an hour, but his cries were not heard. This did not sit well with the small pit-bull, nor the spy. The spy gave up and started the walk back to his side of the battle. A poor idea on his part, though, as that is the opportunity Stubby was perhaps waiting for all along. Stubby launched himself through the air, tearing uniform and flesh off the man’s calf. This, quite quickly, brought the man to the ground. Stubby prevented the man from crawling away or standing back up by sealing his jaw on the man’s buttock, where he remained until the Americans spotted them. The spy was arrested, and Stubby awarded with a custom made “Dog Hero Gold Medal”.

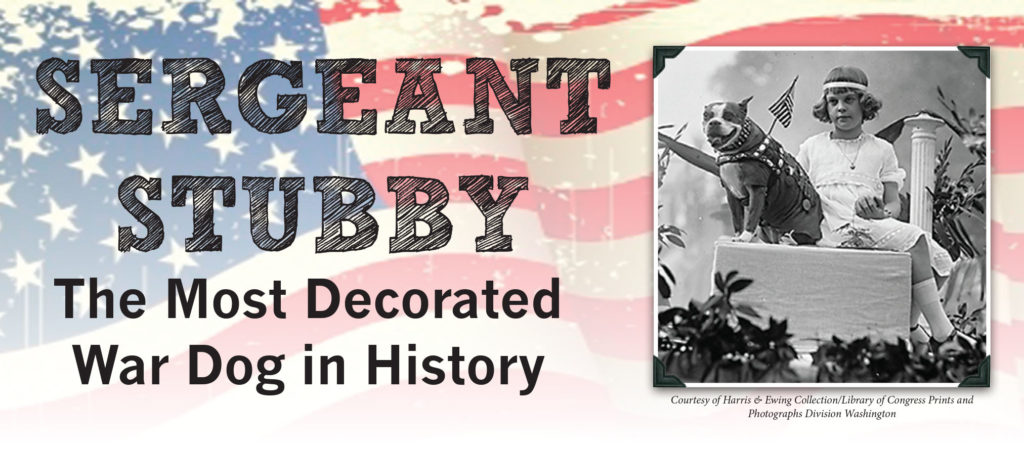

Once the war was over, Stubby would go on to meet three presidents, attend university with his handler, and be an attraction during half time shows. Stubby passed on in 1926, at roughly ten years of age. His body is preserved, along with his uniform and medals, in the Museum of American History in Washington D.C.